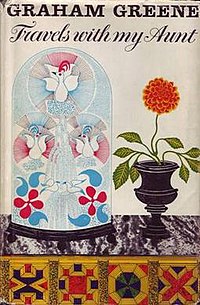

Travels with My Aunt

by Graham Greene

The novel's narrator is Henry Pulling, a conventional and uncharming bank manager who has taken early retirement in a suburban home, and who has little to look for except for tending the dahlias in his garden, reading in the complete works of Walter Scott left by his father, and some bickering with the ultra-conservative retired major living next door. The main choice he could still make is either to remain a bachelor or marry Miss Keene, who likes tatting and who might become his boring and respectable suburban wife.

His life suddenly changes when he meets his septuagenarian Aunt Augusta for the first time in over 50 years at his mother's funeral. Despite having little in common, they form a bond. On their first meeting, Augusta tells Henry that his mother was not truly his mother, and we learn that Henry's father has been dead for more than 40 years.

As they leave the funeral, Henry goes to Augusta's house and meets her lover Wordsworth – a man from Sierra Leone, who is deeply and passionately in love with her despite her being 75 years old. Henry finds himself drawn into Aunt Augusta's world of travel, adventure, romance and absence of bigotry.

He travels first with her to Brighton, where he meets one of his aunt's old acquaintances, and gains an insight into one of her many past lives. Here a psychic foreshadows that he will have many travels in the near future. This prediction inevitably becomes true as Henry is pulled further and further into his aunt's lifestyle, and delves deeper into her past.

Their voyages take them from Paris to Istanbul on the Orient Express; and as the journey unfolds, so do the stories of Aunt Augusta, painting the picture of a woman for whom love has been the defining feature of her life. He finds her to be amoral, contemptuous of conventional morality, having had numerous lovers and speaking forthrightly of having been a courtesan and prostitute in France and Italy. She is also no great respecter of the law, being involved in complicated scams and smuggling and being extremely good at outwitting the police of various countries – in which her nephew becomes her willing accomplice.

Adding to Henry's departure from his middle class mindset is his contact with Tooley, a young American female hippie who takes a liking to him, gets him to smoke marijuana with her and shares with him her own life story, her estrangement from her father who is a CIA operative, her complicated love life, and especially her concern that she may be pregnant. She is, in effect, a younger version of Aunt Augusta.

After tangling with the Turkish police and successfully hiding from them Aunt Augusta's contraband gold ingot, the aunt and nephew duo are deported from Turkey back to England. Henry returns to his quiet retirement, but tending his garden no longer holds the same allure to him. When he receives a letter from his aunt, he finally renounces his old life irrevocably to join her and the love of her life in South America.

By the book's end Henry has adopted Aunt Augusta's amoral outlook, and ends up in Paraguay, taking up the risky but highly profitable life of a smuggler illicitly running cigarettes and alcoholic drinks into Argentina – in partnership with his aunt and her lover Visconti, an escaped collaborator with the Nazis. Having on his arrival been beaten up and imprisoned by the police force of the dictator Stroessner, Henry eventually establishes a mutually profitable relationship with the police, with the help of the local CIA agent Mr. Tooley – the father of the hippie girl he met on the Orient Express. When last seen, Henry is busy making himself fluent in the Native American Guarani language, spoken by many of his smuggling associates, and is preparing to marry the daughter of the corrupt, bribe-taking Chief of Customs, once she turns sixteen. Meanwhile on the other side of the South Atlantic Miss Keene, whom Henry might have married, had immigrated to South Africa and is shocked to find herself adapting to her new, Apartheid-supporting environment and increasingly taking up its prevailing opinions.

As the story progresses it becomes apparent (though only explicitly acknowledged by Henry in the book's final pages) that Aunt Augusta is actually his mother and his presumed mother was actually his aunt. Her re-connection with him at her sister's funeral marked the beginning of her reclamation of her child.