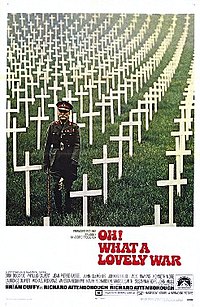

Oh! What a Lovely War

by Len Deighton

Oh! What a Lovely War summarises and comments on the events of World War I using popular songs of the time, many of which were parodies of older popular songs, and using allegorical settings such as Brighton's West Pier to criticise the manner in which the eventual victory was won.

The diplomatic maneuvering and events involving those in authority are set in a fantasy location inside the pierhead pavilion, far from the trenches. In the opening scene, various foreign ministers, generals and heads of state walk over a huge map of Europe, reciting actual words spoken by these figures at the time. An unnamed photographer takes a picture of Europe's rulers – after handing two red poppies to the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, he takes their picture, "assassinating" them as the flash goes off. Many of the heads of state enjoy good personal relations and are reluctant to go to war: a tearful Emperor Franz Josef declares war on Serbia after being deceived by his Foreign Minister, and Czar Nicholas II and Kaiser Wilhelm II are shown as unable to overrule their countries' military mobilisation schedules. The German invasion of Belgium leaves Sir Edward Grey little choice but to get involved. Italy reneges on its alliance with the Central Powers (it joined the Allies in 1915) but Turkey joins them instead.

The start of the war in 1914 is shown as a parade of optimism. The protagonists are an archetypal British family of the time, the Smiths, who are shown entering Brighton's West Pier, with General Haig selling tickets – the film later follows the young Smith men through their experiences in the trenches. A military band rouses holidaymakers from the beach to rally round and follow – some even literally boarding a bandwagon. The first Battle of Mons is similarly cheerfully depicted yet more realistic in portrayal. Both scenes are flooded in pleasant sunshine.

When the casualties start to mount, a theatre audience is rallied by singing "Are We Downhearted? No!" A chorus line dressed in frilled yellow dresses, recruits a volunteer army with "We don't want to lose you, but we think you ought to go". A music hall star (Maggie Smith) then enters a lone spotlight, and lures the still doubtful young men in the audience into "taking the King's Shilling" by singing about how every day she "walks out" with different men in uniform, and that "On Saturday I'm willing, if you'll only take the shilling, to make a man of any one of you." The young men take to the stage and are quickly moved offstage and into military life, and the initially alluring music hall singer is depicted on close-up as a coarse, over-made-up harridan.

The red poppy crops up again as a symbol of impending death, often being handed to a soldier about to be sent to die. These scenes are juxtaposed with the pavilion, now housing the top military brass. There is a scoreboard (a dominant motif in the original theatre production) showing the loss of life and "yards gained".

Outside, Sylvia Pankhurst (Vanessa Redgrave) is shown addressing a hostile crowd on the futility of war, upbraiding them for believing everything they read in the newspapers. She is met with catcalls and jeered from her podium.

1915 is depicted as darkly contrasting in tone. Many shots of a parade of wounded men illustrate an endless stream of grim, hopeless faces. Black humour among these soldiers has now replaced the enthusiasm of the early days. "There's a Long, Long Trail a-Winding" captures the new mood of despair, depicting soldiers filing along in torrential rain in miserable conditions. Red poppies provide the only bright colour in these scenes. In a scene of British soldiers drinking in an estaminet, a Soubrette (Pia Colombo) leads them in a jolly chorus of "The Moon Shines Bright on Charlie Chaplin", a reworking of an American song then shifts the mood back to darker tone by singing a soft and sombre version of "Adieu la vie". At the end of the year, amidst more manoeuvres in the pavilion, General (later Field Marshal) Douglas Haig replaces Field Marshal Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces. Haig is then mocked by Australian troops who see him inspecting British soldiers; they sing "They were only playing Leapfrog" to the tune of "John Brown's Body".

An interfaith religious service is held in a ruined abbey. A priest tells the gathered soldiers that each religion has endorsed the war by way of allowing soldiers to eat pork if Jewish, meat on Fridays if Catholic, and work through the sabbath if in service of the war for all religions. He also says the Dalai Lama has blessed the war effort.

1916 passes and the film's tone darkens again. The songs contain contrasting tones of wistfulness, stoicism and resignation, including "[[The Bells of Hell Go Ting-a-ling-a-ling]]", "If the Sergeant Steals Your Rum, Never Mind" and "Hanging on the Old Barbed Wire". The wounded are laid out in ranks at the field station, a stark contrast to the healthy rows of young men who entered the war. The camera often lingers on Harry Smith's silently suffering face.

The Americans arrive, but are shown only in the "disconnected reality" of the pavilion, interrupting the deliberations of the British generals by singing "Over There" with the changed final line: "And we won't come back – we'll be buried over there!" The resolute-looking American captain seizes the map from an astonished Haig.

Jack notices with disgust that after three years of fighting, he is literally back where he started, at Mons. As the Armistice is sounding, Jack is the last one to die. There is a splash of red which at first glance appears to be blood, but which turns out to be yet another poppy out of focus in the foreground. Jack's spirit wanders through the battlefield, and he eventually finds himself in the room where the elder statesmen of Europe are drafting the coming peace – but they are oblivious to his presence. Jack finally finds himself on a tranquil hillside, where he joins his brothers for a lie down on the grass, where their figures morph into crosses. The film closes with a long slow pan out that ends in a dizzying aerial view of countless soldiers' graves, as the voices of the dead sing "We'll Never Tell Them" (a parody of the Jerome Kern song "They Didn't Believe Me").